“Zofia Rydet on the Sociological Record,” Konteksty, 1997, No. 3–4, pp. 192–198; recording (1988), editing, and titles by Anna Beata Bohdziewicz

Man and His Objects

The idea of the Record was to show man through the objects he possesses. I had previously taken similar photographs, but they were more like reportage. At one exhibition I made the following set: a portrait of a person, and other photographs around it—part of a house, a window, and an object surrounding him. But this was not yet what I was after.

I took photos of huts from the outside, but I wanted to get inside them. I did not have the right equipment, however, neither a flash nor a wide-angle lens. When I bought the equipment I knew at once that this was it. Initially I though that the people would be less important, that they would only sit somewhere off to the side. But it turned out that the people were the most important. The surroundings defined them; they were most essential, and had to sit in the middle. And they had to stare right into the lens. If they were staring off to the side, it ruined my whole concept. When I put the prints alongside one another the effect was utterly different if the pictures were taken consistently. It didn’t matter if the objects were ugly, poor, or pretty. This is sometimes deceptive, because we are dealing with people who do not know how to arrange a space, but the longer I do this, the more I feel sure that the objects that surround a person are what defines him.

The First Huts

Then I reached the conclusion that the idea was also to catch something that was fading away. I soon noticed that these huts were quickly vanishing, they were changing dramatically. I started with the poorest ones. Perhaps this was because the first hut I photographed was so horribly poor. It was inhabited by three old people, and that hut was terribly small! A kitchen right in the middle, two sacks, and all of it plastered with pictures clipped out of various things, from candy wrappers and packages. The wardrobe, the chest, all of it was plastered. The need for beauty in these people was very refined, they needed it and sought it out. That convinced me that objects often say more about a person than he does about himself.

So that was the first house. The second one was right next door. It was less interesting. It was inhabited by a woman who rented rooms to summer vacationers and, as such, her taste was somewhat affected. On one wall there was a picture of the Holy Mother, by that a cross, and on the other side there were some cut-outs from a newspaper with a portrait of Gierek and Brezhnev.

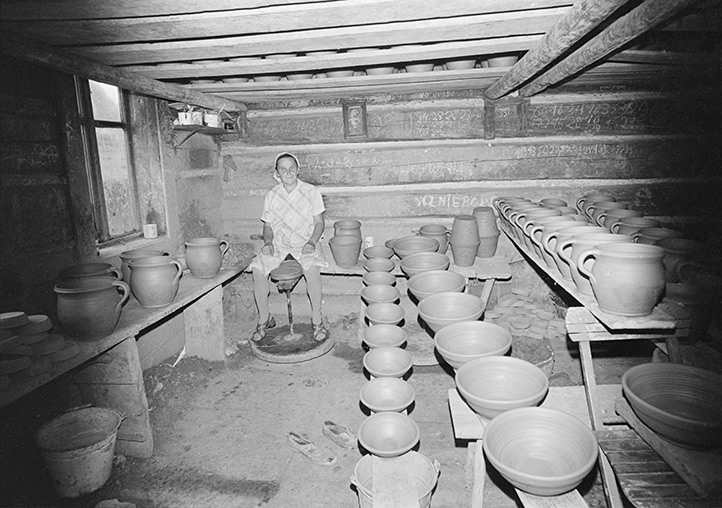

It was stuck up there with a big pin. So I asked her: “Helena! You have the Holy Mother, a cross, and here Gierek? How can this be?” And she said, “Come on! I’d rather stick it up his ass, to get him out of here, but I’ve done it on purpose. The Holy Mother is my heart, but when guests come here for lunch, they can see the ruler’s there. If they want to do something to me I can show them what they want, I have Gierek, I have Brezhnev!” And the third was the home of a potter. I took a lot of photos there, both in the home and in the pottery workshop. They were a lovely couple. He was old and ill, and he died the following year.

The First Year

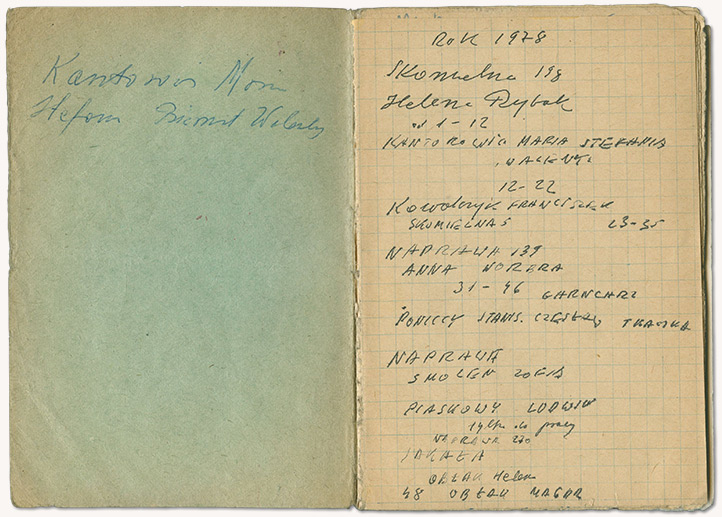

1978 was the most fruitful. Day after day, rain or shine, Kaśka [Katarzyna Augustyńska, the granddaughter of Tadeusz Rydet, Zofia Rydet’s brother] and I ran early in the morning to catch the bus, and then spent the whole day on foot, without eating, unless someone gave us some food or we found a shop where we could buy something. The first year was a bumper crop. I went to Gliwice, I developed it all, I made the first prints, and I was utterly astonished. I often saw the beauty not in the moment of taking the photograph, but later, when I was retouching the prints. I was simply delighted. When I entered a hut I was tense and often didn’t see many things, though some I caught in the first instant. So I thought “yes, this is it!” There was a fairly important symposium at the time; there was Czartoryska, Gardzielewska, and other people. And I showed them the pictures. Everyone said that they were very good, very interesting. That helped me a lot, it confirmed that what I was doing was worthwhile. And then it all seemed fascinating to me. I wanted to have various homes. So I started photographing homes of acquaintances in Gliwice. But that was rather awkward, because first you had to drink a cup of tea, chat a bit, and then they wanted copies of the pictures. I was also in a dorm, where everyone has the same rooms, and yet every “apartment” was different. The rooms of students from the country and the city differed enormously.

The First Exhibitions

I first showed the Record in Gorzów in 1979 [X Gorzowskie Konfrontacje Fotograficzne, Gorzów Photographic Society, Regional Museum]. Jerzy Olek was showing the beginnings of his elementary photography, Dłubak was king. There was a whole big room with their photographs. Olek’s black-and-white dots with various captions. The whole room was conceptual. And in those small rooms to one side was my Record. But then what happened. The crowds, including my fellow photographers, moved quickly through the other rooms and then stood a very, very long time in front of my pictures. They stood there and looked, then they asked questions, and they said: “Ah! They’re brilliant. Marvelous!” I had thrown in a few pictures of the intelligentsia, and the people told me: “You should have added a few more of those fools.” “What fools?” They were speaking of the intellectuals. Because the homes of the intellectuals looked entirely different. I had, for example, a picture of an empty house with only a wall unit and a single picture, and an intellectual was sitting there with a truly foolish expression. They are really very unfortunate, because they can’t decorate their houses as they please. They themselves don’t know what to hang on their walls. Either they put nothing there, or in many cases, they have various pretty landscapes. And so at that time, in Gorzów, Andrzej Baturo came up to me with some reporters from Warsaw and they said: “Well, aren’t you brave! And if we were to do a big exhibition of reportage photography, would you take part, would you have the nerve?” And I said: “Why shouldn’t I have the nerve?!” So then Baturo did do an exhibition like that [The 1st National Review of Sociological Photography in Bielsko-Biała, 1980]. The exhibition was brilliant, but very brief. I sent in many of my photographs, in sets of four works apiece: four women, four men, four children, etc. I spent a long time considering each set, every set has its own significance, presenting a particular region of Poland. And they mixed them all up, and papered a whole wall with those photos, with no gaps in-between them, they crowded in all those various people and interiors. I couldn’t look at it! That was an enormous mistake displaying them like that, because a great deal depends on how these pictures are shown. I was irate toward them for that, but they said that it was more interesting that way. For me it wasn’t. They did me a great disservice.

The whole series was supposed to have had a totally different title, but I don’t remember what it was. I think it was Urszula Czartoryska who came up with Sociological Record. Though this is not an academic piece, and I would not have wanted it to be “academic.” I have the old title somewhere in my notes, but now I can’t change it, the name has stuck.

The Growth of the Series

At first I photographed only one wall that had everything that was important to me. Now I photograph four walls. The whole house, as it were. If I were to do an exhibition now, I would do everything completely different. I would make a triptych, where the same person would sit here, and there, and there, and there. And it would all make up a home. Moreover, I would also want to include large photographs depicting the whole of a village and the landscape around. And sets. A hut from the inside and outside, as I showed it. Then others. A hut, a fragment of a hut from the outside, perhaps a number or a decoration. Then an interior, and here a portrait perhaps. There has to be more diversity, not only uniform arrangements. And there have to be various formats.

The portraits are also essential, which is why I took them. I was not yet certain if these would be portraits taken from above, or some other way. The ones from above were supposed to be in special frames, like from holy pictures, like the portraits of saints in churches, elongated and deformed. I wanted to take ones like that. That is why I photograph old and ugly people, because I almost wanted to turn them into saints, then their faces take on an entirely different form of expression. I also have a series of portraits of women in doorways, standing there in six ways, you can see a piece of roof, a piece of hut. And then I also made sequences and layouts from them, making them into a whole composition.

I also have various kinds of stories with windows, very lovely ones. Windows from the inside. In the old huts there’s always a table standing between two windows. There are always flowers in the window boxes, and on the table is everything that the person needs—glasses, figurines of some sort, sometimes very humorous objects. They make up still lifes.

But the windows themselves are sometimes very pretty. I also take photographs of roads with the most interesting village names. I have thirty or forty such pictures, perhaps not quite enough yet. Oh yes, and I have the “Myth of Photography.” That’s quite beautiful. I have also thought—I noticed it just recently—that the vestibules have a lot of personality. But now it’s too late, I don’t know if I’ll be able to find many anymore. All this goes beyond me, even in formal terms. But I keep seeing something new, and then I want to make a whole series. Since last year, I’ve begun going mad for professions. I also photograph the signboards for every occupation. Signboards are very interesting. Sometimes I even cheat a bit, because if I have a good interior but no signboard to match, I take one from somewhere else.

I have also started taking office photographs. It’s fascinating how everyone sets up a corner for himself. I also began taking photographs in buses, always from the seat behind the driver, into the mirror that reflects his face and everything all around, all those decorations.

I keep having new ideas, and I have to take the pictures right away, it’s an addiction, like vodka for an alcoholic. I have thousands of rolls of film I haven’t even made prints of. All my life I have collected things. First I collected children’s coloring books, then pictures of saints, then cards, and stamps, I have some gorgeous collections to this day. It’s very deep in my nature. And there is something of this in the photography as well.

The Picture in the Polish Hut

I could show the history of the picture in the Polish home—and this would be quite fascinating, very instructive. So, we have those rows of pictures in village and mountain huts. Then, I don’t know how it happened, there are also elongated photographs, the Holy Mother, angels, in large frames, colorfully painted. There are also deer, and sunsets. And then it’s much the same all across Poland—Holy Mothers and Hearts of the Lord Jesus printed sometime before the war, also in big frames. Then come the tapestries, of all different kinds. In Podhale you have something else, it’s Chicago, things you’ve never seen before! Big, wall-sized tapestries. Made in the USA, perhaps. Sunsets or the Last Supper, portraits of the Holy Mother, and scenes from mythology. There are also hand-painted ones, like canvases, angels, with Christ in the middle, and inscriptions. And then there are the tiny tapestries, for the kitchen mainly, with very pretty inscriptions. For example: “A good husband always helps his wife.” There’s the wife baking a cake, and her husband is sitting beside her playing the guitar. Marvelous stories!

(...) Why do I do it?

I have so many pictures, but I sometimes wonder: Is there any sense to it all? Why do I do it? Nobody wants them. It’s all so interesting, and I can’t exhibit it anywhere. Because there’s no real venue for it. But every summer, like a dog returns to his kennel, I return to this.

(Recorded in August 1988.)